The

greatest figure of Christian Humanism

Acclaimed “Prince of Humanists”,

Erasmus of Rotterdam was considered the greatest figure of Christian humanism.

Humanists no longer accepted the values and ways of being and living of the

Middle Ages. The source of aspiration of these authors was the cultural

production of Greco-Roman antiquity.

In 1492 he was consecrated a priest,

even criticizing the monastic life and the characteristics that he considered

negative for the Catholic Church. In 1495, Erasmus secured a scholarship to

Paris and entered the famous College of

Montaigu, annexed to the Sorbonne. There he studied for the degree of

Doctor of Theology. Dissatisfied with hostilities to the new ideas coming from

Italy, he dropped out of the course. He began teaching seeking his

independence.

His anticlericalism manifested itself

in the form of a scathing critique of the religious life of his time, more

specifically, of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, particularly the Roman curia.

Humanists also disparaged the medieval scholasticism so widespread in their

day. They preferred practical matters related to society and civic life to the

philosophical and rationalist discussions that had taken hold in European

universities.

Dedicated to reading the classics, he

became one of the most cultured men of the time. For him, pagans like Cicero

and Socrates deserved the name of saints much more than many Christians canonized

by the pope. “Saint Socrates, pray for us”, was his famous motto.

All healthy education is education without religious control

Forerunner of Church Reformation

In 1499, in England, he met Thomas

More and they became lifelong friends. He studied Greek at Oxford and became

friends with the humanist John Colet. Erasmus idealized, together with Thomas

More and Colet, the project of restoration of theology, with new editions of

the sacred texts, from Greek and Latin.

Colet accelerated Erasmus' ambition to

be a "primitive theologian," one who would expound Scripture not in

the argumentative manner of the Scholastics, but in the manner of St. was still

understood and practiced. He returned to the continent with a Latin copy of the

Epistles of St. Paul and the conviction that “ancient theology” required

mastery of Greek.

In 1500, he published Adagios, a collection of Latin

quotations and proverbs. For the time, the work represented the maximum in

popular literature and made the name of the author famous.

The wandering life took him back to

Paris, where he devoted himself to the study of the New Testament. He returned

to England in 1505. In 1506, already in Italy, he obtained the “papal

dispensation of obedience to the customs and statutes of the Convent of Steyn”.

In Rome, he frequented the intellectual circle of Pope Julius II, but confessed

that he was horrified by the pope's triumphal entry into Bologna. Convinced

that the bellicose Julius II was Caesar's successor and not Christ's, and with

the expansion of papal power, he felt the need for reform in the church.

Erasmus' greatest theological contribution and the real spark of what would become the Protestant Reformation was, of course, the publication of his edition of the New Testament in Greek, in 1516. He intended, with it, to replace that of Jerome. However, his ambition to become a revived Jerome was thwarted by the Council of Trent, which in 1559 condemned the Latin translation. Even so, he achieved immortality, as his editing of the Greek text was the basis for different Protestant translations and became known as the Textus Receptus.

Johann Froben, his editor, as the

first published Greek edition, marketed Erasmus’ edition. Erasmus expressed, in

the preface to the work, that he wanted every person to have the chance to read

the Bible.

Although it is considered the first

modern edition of the New Testament in that language, a bilingual (Greek and

Latin) edition of the entire Bible, which was printed two years earlier and

became known as the Completeness Polyglot, preceded it.

His effort to publish the New

Testament in the original language came about because of the humanist

influences that existed at the time. This Renaissance movement, which began in

Italy, fueled enthusiasm for the study of classical art. For this reason, there

was a peculiar interest in “returning to the sources”, prioritizing literary

works in their original language.

He possibly, contributed the most to

laying the foundations of the Protestant Reformation movement. While he gave

significant impetus to the study of the Bible, he also exposed monastic

fanaticism and ignorance, as well as ecclesiastical abuses.

Despite this, he never declared

himself a reformer in the Protestant sense of the term. He even announced “war”

against Luther. Although he continued to disagree with Rome in many respects,

he did not dissociate himself from it. His desire was a reformation within the

church and the papacy.

Erasmus anticipated in his literary

works several concepts that would later be considered typical principles of the

Protestant Reformation, such as religious individualism; that is, the notion

that true religion consists of inward devotion rather than outward symbols of

ceremonies and rituals.

Because of his positions in relation

to the Church, he acquired enemies on both sides, which brought him bitterness

at different times in his life. However, none of this prevented him from

becoming highly respected throughout Europe. His life, works and theological

opinions are necessary objects of study for anyone who wants to know more

deeply the origins of the Protestant Reformation.

Erasmus versus Luther

Erasmus did not attach great importance to Luther's 95 theses nailed to a church door, but he agreed with the criticism of the sale of indulgences. In many of his works, he had already formulated Luther's convictions, against the mechanical practice of rites and the fetishistic cult of saints and relics, which replace religion based on piety.

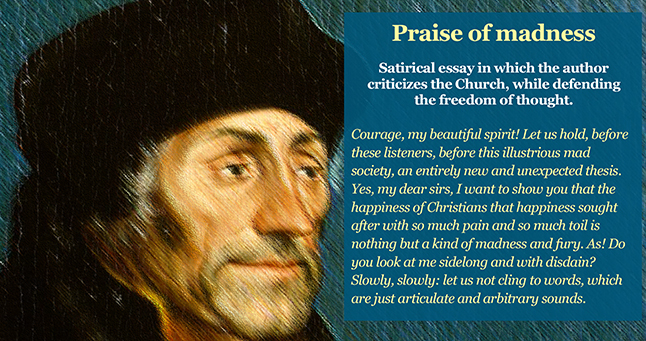

Praise of Madness

Installed in the house of his friend Thomas More, in London, he wrote, in 1509, Praise of Madness. The work brings a critique made in an ironic, but objective and direct way, to the customs of the Christian faith preached by the Catholic Church of the time, without attacking anyone personally. Erasmus presents Madness as a goddess who calls herself the great responsible for the delights that the human being wants to obtain in the world. In addition, it is Madness who speaks in his name, who places herself in an unassailable position and allows him every audacity.

Indignant at the pagan luxury of the

popes' cities, where open criticism could lead to the stake, Erasmus used his

madness to denounce all these abuses. He used to say how many material

treasures the holy fathers would abandon, if judgment one day took possession

of their spirit. Without a doubt, Praise of Madness is a masterpiece. It was

published in 1511 and dedicated to his friend Thomas More.

While in Paris, Erasmus became known

as an excellent scholar and speaker. One of his pupils, William Blunt, Baron

Montjoy, granted him a pension, allowing him to adopt a life of independent

scholar, from town to town teaching, lecturing and corresponding with some of

Europe's most brilliant thinkers.

Erasmus died without coming to an

understanding of many truths that would be restored during the following

centuries. As the Bible mentions in Proverbs 4:18, the path of the righteous is

like the light of dawn, which shines brighter and brighter until the perfect

day. Although he was a great scholar and became the great expression of

Christian humanism at the time, he also had his limitations. However, it is not

possible to measure the value of his contribution, especially that of his

publication of the Greek New Testament. God, in His infinite wisdom, knows how

to use each person's talents.

Works by Erasmus of Rotterdam

Erasmus was a wise and avid reader. He

wrote several literary, philosophical and religious works of which the

following stand out:

- Christian Knight's Handbook

- Praise of Madness

- Christian Parents

- Family Colloquiums

- The Navigations of the Ancients

- Preparation for Death

Although Erasmus is not considered by

many scholars to be a reformer in the strictest sense of the term, his

influence on many reformers cannot be denied. His interest in the classical

arts and languages, as well as his emphasis on education as a means of

overcoming the low morality of his day, markedly influenced the theology of the

Reformers and their message that each person should know the Bible for himself.

On his deathbed, he was visited by

three friends, which reminded him of Job's experience. Erasmus died on July 12,

1536, and is buried in Basel Cathedral, Switzerland.